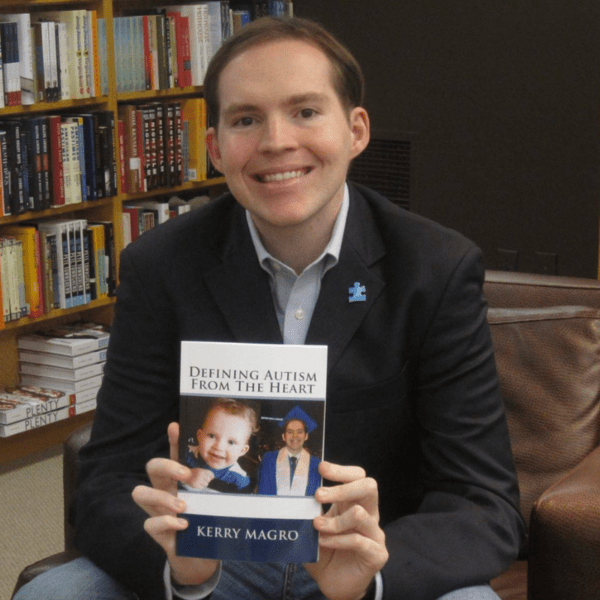

This guest post is by Alyssa Thierauf, a young woman who is diagnosed with autism and is currently attending Miami University majoring in Games + Simulation while taking courses in the Game Art and Game Studies tracks. She is focusing on the more creative aspects of game development, learning how to create art and stories for games. Alongside this, she has declared a minor in anthropology to further understand other humans and cultures. Thierauf is applying for the Spring 2024 Making a Difference Autism Scholarship via the nonprofit KFM Making a Difference started by me, Kerry Magro. I was nonverbal till 2.5 and diagnosed with autism at 4, and you can read more about my organization here. Autistics on Autism: Stories You Need to Hear About What Helped Them While Growing Up and Pursuing Their Dreams, our nonprofit’s new book, was released on March 29, 2022, on Amazon here for our community to enjoy featuring the stories of 100 autistic adults.

A few years ago, I was informed of a debate surrounding the supposed “Pandora’s Box Paradox”. It follows the Greek myth in which Pandora opens a box ignorant of the fact that it held all the evils and despairs of mankind, releasing them into the world. All that was left in the box was a small light named “Hope”. The debate calls into question the reason Hope was left behind: was it because people must keep hope close in order to persevere, or is it because hope is the greatest evil of all? My answer is that the title of the question lies, and there is no paradox within the scenario.

In fact, calling this a paradox is a mockery to its definition by Merriam-Webster, which reads, “one (such as a person, situation or action) having seemingly contradictory qualities or phases”. Hope is a nuanced creature whose wickedness is merely determined by the quantity one has. It is similar to how the seven deadly sins are not inherently sinful, but merely a human quality. The sins become deadly, per se, when one has too much or none at all. In regard to hope, it could be considered the eighth sin with this logic. When there is too much hope, people only rely on faith and wait for what they wish to come. When there is a lack, nihilism and pessimism set in. In both scenarios, it becomes the worst things for humans to do: inaction and complacency. Hope is evil when it makes one believe that nothing can change, or that someone else can change it for them.

Of course, one is most likely wondering what this has to do with me, the teenager who decided to make a large chunk of her essay about the deconstruction of a paradox with a logic not often understood. The truth is, this false paradox applies to the greater world more than one may think. It’s more than something the protagonist of a children’s television show shouts when they are fighting the main villain as the music builds in the background. Hope can be found in our daily lives. My parents wanting a lake house to retire in, my brother trying out for the high school soccer team, myself and hundreds of others submitting our most vulnerable moments to scrutiny for aid in college; these are all examples of people relying on hope. The paradox would have come in if my parents didn’t save up to buy a small, affordable house close enough to the lake that they could renovate to their liking, or if my brother didn’t train every day over the summer leading up to the try-outs, or if us applicants did nothing and relied on faith that we would get the scholarship prize. Now that I’ve given you an example, I have a small hope that before one continues reading that one ponders for a moment where this paradox leeches into one’s everyday life.

For me, the paradox of hope is found in video games. They have provided a safe space for me to go when I get stressed or overwhelmed for as long as I can remember. Yet, games also keep me in a basement, neatly tucked away from the world. For the hope that plagued me was for something I struggled with: connection. I know the root of my struggles is in my diagnoses of autism and ADHD, the way that my tone doesn’t really vary; my neutral facial expression that gets read as upset; being unable to read the room; or possibly how I often speak too quietly or quickly to be heard. In any case, bonding was much easier with a character that had set dialogue and actions than a real person with inner thoughts and depth. It even came to the point where I stopped trying, and settled with connecting to the pixels on the screen. After all, if a character doesn’t like you, the plot deems it necessary to explain why. Since the program has no eyes to look at me with pity, no ears to be filled with false notions about how my mind works, no nose to turn up at me, no mouth to give shallow compliments that merely apply more stress and pressure: I was free. The game took me for me.

If one can’t tell, most of that previous paragraph was in past tense for a reason. That was when my hope for connection could be deemed purely evil. While there are many others like me who hide themselves inside of video games, it isn’t the games’ fault. Plenty of people have a healthy connection with games. The main root of the problem has already been stated: isolation and want for connection. I began to realize this when I started making acquaintances in robotics (I wouldn’t call them friends at that point). As my connection to real people expanded beyond my family and the one friend I kept from elementary school, I became aware of how tightly I gripped the controller. As these acquaintances became friends, I started to loosen my grip. It is a slow process of course, I wouldn’t expect an unhealthy attachment to leave after a few mere years, and I still hit slumps where the screens become my best friends for sometimes days. However, it has become better. I don’t immediately log into a game after classes anymore. I turn off the screen when my eyes get tired, and I let myself take more than a month to complete a game. Most importantly, I don’t let the slumps take over as I hope to form strong bonds with others by moving forward.

Follow my journey on Facebook, my Facebook Fan Page, Tiktok, Youtube & Instagram.

My name is Kerry Magro, a professional speaker and best-selling author who is also on the autism spectrum. I started the nonprofit KFM Making a Difference in 2011 to help students with autism receive scholarship aid to pursue post-secondary education. Help support me so I can continue to help students with autism go to college by making a tax-deductible donation to our nonprofit here.

Autistics on Autism: Stories You Need to Hear About What Helped Them While Growing Up and Pursuing Their Dreams was released on March 29, 2022 on Amazon here for our community to enjoy featuring the stories of 100 autistic adults. 100% of the proceeds from this book will go back to our nonprofit to support initiatives like our autism scholarship program. In addition, this autistic adult’s essay you just read will be featured in a future volume of this book as we plan on making this into a series of books on autistic adults.