This guest post is by Dano de Waal, who attends the University of the Western Cape. They are an advocate for the Spring 2025 Making a Difference Autism Scholarship via the nonprofit KFM Making a Difference started by me, Kerry Magro. I was nonverbal till 2.5 and diagnosed with autism at 4 and you can read more about my organization here.

Autistics on Autism the Next Chapter: Stories You Need to Hear About What Helped Them While Growing Up and Pursuing Their Dreams was released on Amazon on 3/25/25 and looks at the lives over 75 Autistic adults. 100% of the proceeds from this book will go back to supporting our nonprofits many initiatives, like this scholarship program. Check out the book here.

From the time my mom threw me a Nemo-themed party for my fourth birthday, I fell into an immersive admiration for marine life. Particularly for sharks. This was not a fleeting fascination. Sharks had become a symbol of my life. Similarly to the portrayal of sharks in movies such as JAWS, misunderstandings and misinformation detailed my journey. Growing up, I could convince myself that I was an adopted robot. Disconnected from those around me. As a child, I was unable to vocalise this feeling. It became increasingly frustrating to understand why social interactions seemed to be a puzzle I could not find the pieces to even initiate an attempt to solve. Birthday parties of my peers frequently involved instances of exclusion or a platform for bullying. I knew I didn’t belong there. I knew the invites were out of courtesy. My difference became undeniable to me and my peers, yet its causality could not be identified.

A remarkable event occurred during the year that I was about twelve years old. This moment has been engraved so vividly in my mind. I can recall the precise movement of every head turn, the smell of salt water, and the damp sand sticking to my feet. During a family beach outing, someone had casually mentioned to my mom that I might have ADHD. My mother, my fierce protector, immediately dismissed the idea. I understand now that her reaction was shaped by a fear of a label that rendered me defective rather than different. However, that comment appeared as an epiphany submerged in guilt for me. It didn’t make me feel defective—it, contrarily, felt as though a spotlight had caught my behaviours red-handed. Finally, I was provided with a potential explanation for the dissonance that had become my second nature. Although, despite the glimmer of recognition, a diagnosis failed to materialise.

About six years thereafter, I started university and had a passion for working with learners with ASD. I am not able to recall why or how this passion arose. My, then, psychologist suggested I see a psychiatrist to obtain official diagnoses. Yet, it was only once I became involved with the Students with Disabilities Forum as a Student Parliament Representative that I had a need to provide proof of diagnosis. I then made my first appointment with my psychiatrist. At the age of twenty-one, I was officially diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (with more that I would not like to disclose).

This diagnosis did not feel like a confinement or a depiction of what my life would be limited to. This diagnosis was initially a relief of understanding. Followed by a guilt of how my behaviours may have impacted the people around me. Every time I can remember being confronted by people critiquing my actions and not understanding why my actions were wrong. Or when I attempt to provide context for understanding of why I did or said certain things, and I am shut down by accusations of excusing my behaviours. I never meant to excuse or justify what I did. I only wanted to provide context as to why I felt that my decision made was appropriate in that moment.

An example of this: An old friend from high school had gotten a back tattoo which included a big circle. When I (with kind intention and the idea that I would appreciate if someone pointed out a mistake on a tattoo that I could alter within the near future) messaged said friend to say that the circle was slightly crooked. The response to this message was met with disdain. My aim to explain that my observation stemmed from a genuine friend trying to help another only acted as paraffin to her fiery response.

Suddenly, these occurrences made sense. Not as to exactly what my negative position had been but rather that my understanding of social interactions was viewed differently from my peers. I then decided that I would ask for clarity as much as possible. I have two close friends to whom I would ask if I correctly understood an instruction or social cue or, I would whisper my responses to friends, almost as a peer review, for appropriateness. Understanding the diagnosis allowed me to understand my own difference in perspective, allowing me to navigate my interactions with enhanced success.

Following my diagnosis and the understanding of its implication, I came to realise that I could utilise my ASD as an advantage in my career. ASD is an invaluable asset. ASD allows me to relate to individuals with ASD through my insider perspective. As an aspiring Educational Psychologist, this insightful understanding cultivates advanced appropriateness of the approaches implemented in my practice. It facilitates a more rapid identification of the cause of a client’s distress as compared to the efforts of a neurotypical Educational Psychologist. I discovered this while working as a teaching assistant at a school for learners with ASD. I was not merely assisting in the everyday school activities; I understood my learners. I knew how it felt when the summer heat was so overwhelming that it felt like your head was heavy, your chest was unable to expand enough to take a breath, and your clothing felt like ants crawling on your skin. I understood that a small change like a new juice in your lunchbox would dysregulate your emotions. And that chucking the bottle across the room was but a way to communicate your frustration. We are not trying to give people a hard time; we all have hard times that we present in our own ways.

My journey has taught me that true inclusion is not about ensuring that learners with ASD are kept separate from the mainstream education system. It is about cultivating environments which accommodate and support the diversity of the human populace. Through my career, I am committed to advocating for policies and practices that reflect a deep understanding of ASD and its complexities, particularly in the South African context.

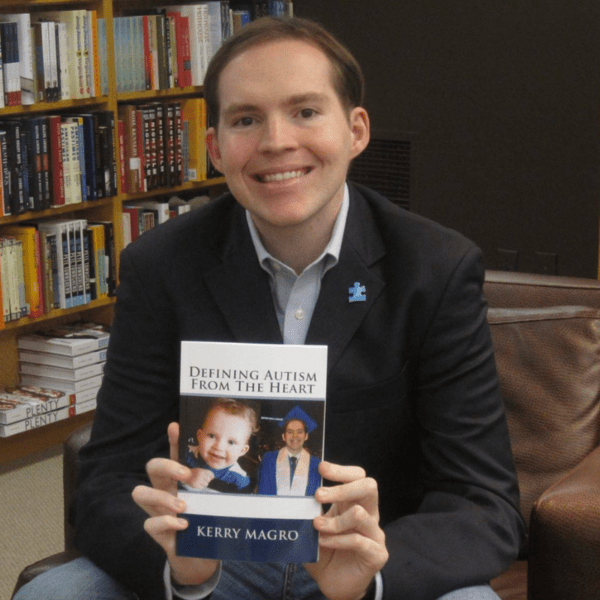

Kerry Magro, a professional speaker and best-selling author who is also on the autism spectrum started the nonprofit KFM Making a Difference in 2011 to help students with autism receive scholarship aid to pursue a post-secondary education. Help us continue to help students with autism go to college by making a tax-deductible donation to our nonprofit here.

Also, consider having Kerry, one of the only professionally accredited speakers on the spectrum in the country, speak at your next event by sending him an inquiry here. If you have a referral for someone who many want him to speak please reach out as well! Kerry speaks with schools, businesses, government agencies, colleges, nonprofit organizations, parent groups and other special events on topics ranging from employment, how to succeed in college with a learning disability, internal communication, living with autism, bullying prevention, social media best practices, innovation, presentation best practices and much more!