This guest post is by Maxwell Hutchinson, a young man on the autism spectrum who was diagnosed with ASD and has been accepted into West Chester University of Pennsylvania. Maxwell is applying for the Spring 2022 Making a Difference Autism Scholarship via the nonprofit KFM Making a Difference started by me, Kerry Magro. I was nonverbal till 2.5 and diagnosed with autism at 4 and you can read more about my organization here. Autistics on Autism: Stories You Need to Hear About What Helped Them While Growing Up and Pursuing Their Dreams, our nonprofit’s new book, will be released on March 29, 2022 on Amazon here for our community to enjoy featuring the stories of 100 autistic adults.

When we step back and view our standards, our society, and ourselves from the perspective of an outsider, it becomes apparent how deeply misguided our common morals and values are at their core. By our nature, we are burdened with a hunger to categorize all that exists on a primal basis of “familiar” and “unfamiliar,” too often synonymous with “good” and “bad.” We see differences in a person, and whether it is in the way of race, behavior, or otherwise, those differences become all that we see. The person becomes nothing to us but whatever discomforting unfamiliarity we associate with them.

The unfortunate truth is that several individuals on the autism spectrum become the victims of this misjudgment. While I feel fortunate to have been diagnosed with but a very moderate form of autism, I too have seen the struggles of life that arise for myself and others. From my experience, however, I have found that for many people, the key to overcoming both the reductive potential of the disability and debilitative, exterior responses to it is to recognize that, on a fundamental level, such stressors simply do not matter.

I was first diagnosed in the second grade; what I remember about that day most vividly was my reaction. I heard the word pass through the doctor’s lips, and images flooded my brain, associating myself with imaginary visions of autism. It terrified me, the knowledge that I was being categorized for what many would dub a ‘mental deficiency.’ This is exactly the problem.

What shameful fears I had, of instantly reducing myself to such a state and inherently expecting a future of intellectual hardship. Despite my initial emotions, however, this marked the beginning of my gradually developed understanding that perspective makes all the difference. I also was diagnosed with ADHD, a condition long misinterpreted by some of my academic advisors as minor incompetence, often reflecting on my self-doubt.

While I made use of services to alleviate this issue, my natural lack of focus consistently set me apart from others on a level even I could not ignore. Additionally, my social skills were weak; my mental processing speed was sluggish. As I would come to learn, however, there are various forms of ‘intelligence’ or ‘competence,’ and I found myself excelling in the way of standard academic performance, achieving nearly constant straight-A grades and even proving myself worthy of induction into the gifted program.

My participation in the gifted program evolved significantly over time; despite its humble beginnings in the area of literary analysis at an elementary school level, I later engaged in thought-provoking activities that spurred my imagination and mental capacity. My middle school robotics course allowed me to blend my interests in engineering, built on prior understanding, with novel areas of study, allowing me to tear down preset barriers placed upon myself and defy common notions of what autism enables.

My high school experience presented further academic fruition with erudite coursework and self-guided projects that helped me to determine my future career paths. Overall, I held the gifted program in high regard for its unending ability to capitalize on my strengths whereas some may have diminished me on account of weaknesses.

Regardless of my intellectual capacity, I faced daily tribulations in the merest, seemingly basic skills of life. From my first diagnosis to my final year of middle school, I was accompanied by a faculty aid who assisted me in organizational skills; I would assert now that such measures impacted by a gradual onset of independence such that I no longer required them after a time.

Through elementary school, I would also attend brief classes, apart from my primary lessons, which were tailored to establish my fundamental capabilities. Broader Strategies classes in middle and high school replaced these sessions, which to me seemed a welcome transition. The previous classes concerned trivial topics or those I already understood; my ability to switch from pencil-point to eraser with one hand or my grasping of common figurative expressions, to name a few.

While I understood their kindly intentions, I believe the lessons caused more harm than good. Rather than helping me to “assimilate,” they merely underscored for me the myriad ways in which I was “wrong” that I had never before considered. At my age then, such reminders felt like emotional bullets. Even my academic strengths, as well, could become a strain on my confidence when I encountered significant difficulty. Oftentimes, when I did not know what to do, I would panic and begin to loathe myself for my inability to solve the problem.

As time progressed and my future emerged on the horizon, I also worried over the uncertain life that awaited me. I doubted my skills, viewing my array of minor individualities as significant setbacks, for I feared that my intelligence would find no practical use in the absence of effective social skills, and I believed that what progress I had made to improve my interpersonal relationships had been insufficient.

Nonetheless, I conceived goals by which I would proceed to abide to secure for myself a bright future. With my natural skill and curiosity in science, I resolved to study however necessary to become an astronomer. My diverse set of interests and talents also opened possible career paths as a marine biologist or even an author, as I spend much of my free time composing my own enticing, convoluted stories.

To this day, I strive to grow beyond the constant challenge of self-doubt that plagues my mind and degrades my confidence. There shall always be situations in which others simply have an innate advantage over me or in which I face undue judgment for my weaknesses. One cannot change the nature of life or the baselines of the human mind.

I have learned, though, that provided a resolute, supportive community such as my ever-encouraging family, one can take pride in one’s strengths without cowering in fear of one’s vulnerabilities. Most profoundly, however, one must have the faithful resolve to persevere.

Follow my journey on Facebook, my Facebook Fan Page, Tiktok, Youtube & Instagram,

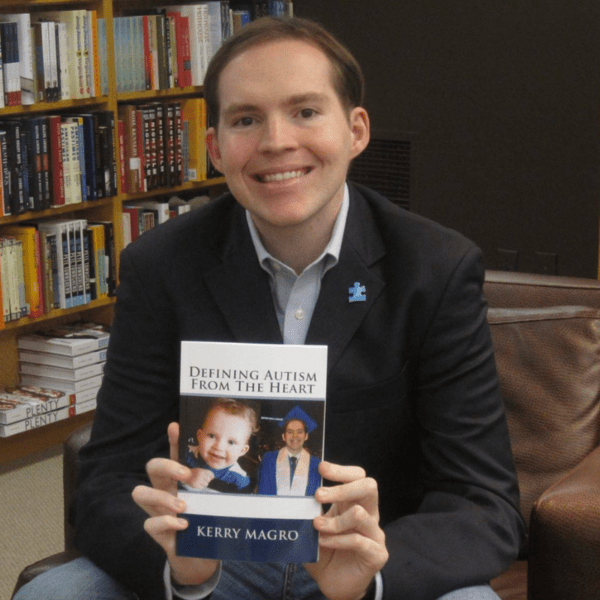

My name is Kerry Magro, a professional speaker and best-selling author who is also on the autism spectrum that started the nonprofit KFM Making a Difference in 2011 to help students with autism receive scholarship aid to pursue post-secondary education. Help support me so I can continue to help students with autism go to college by making a tax-deductible donation to our nonprofit here.

Autistics on Autism: Stories You Need to Hear About What Helped Them While Growing Up and Pursuing Their Dreams, will be released on March 29, 2022 on Amazon here for our community to enjoy featuring the stories of 100 autistic adults. 100% of the proceeds from this book will go back to our nonprofit to support initiatives like our autism scholarship program. In addition, this autistic adult’s essay you just read will be featured in a future volume of this book as we plan on making this into a series of books on autistic adults.